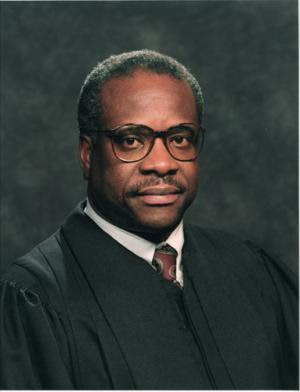

Clarence Thomas

Biography:

Clarence Thomas has lived a life riddled with irony and contradictions. Although he has opposed racial preference and affirmative action programs, he nonetheless benefited from them. As a young student, Thomas entered the College of the Holy Cross, a Jesuit institution in Massachusetts, after the school began a black recruitment program. Thomas was the beneficiary of a similar minority program a few years later at Yale Law School. As a young lawyer, Thomas aimed at a career outside the ambit of civil rights. However, for his effort, he earned appointment as the heard of the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. And racial preference ultimately explained Thomas's appointment to the Supreme Court. Although President George Bush stated that he chose Thomas for his legal qualifications, it would take conscious effort to ignore the political pressures on Bush to name a black candidate after the retirement of Thurgood Marshall, the Court's first and only black justice. Thomas' nomination itself threw traditional political loyalties into disarray. Liberals, including the NAACP and Congressional Black Caucus, did not know what to do. Their desire to see a black justice on the Supreme Court competed with their disapproval of Thomas' conservative views. In the end, fearing that a black voice will legitimize the arguments of many white conservatives, the liberals sought to block Thomas' nomination. Conservatives, on the other hand, embraced Thomas. His unlikely supporters included Sen. Strom Thurmond, who had built his earlier political career on a segregationist platform. Finally, Thomas's confirmation hearings cemented the impression that his nomination served to fill an unspoken racial quota on the Supreme Court. Thus, Clarence Thomas joined the Supreme Court under the very shadow of affirmative action that he sought to avoid.

Clarence Thomas was born on June 23, 1948, in Pin Point, Georgia. The second child and first son of M.C. Thomas and Leola Williams' three children, Thomas spent most of his childhood without his father who abandoned the family early in Thomas' life. Thomas grew up in poverty. The Pin Point community he lived in lacked a sewage system and paved roads. Its inhabitants dwelled in destitution and earned but a few cents each day performing manual labor. Thomas's mother tried hard to take care of Thomas and his brother and sister. She worked as a maid and collected from church charities to support her family. At age seven, Thomas' mother decided to remarry after the family's wooden house burned to the ground. Thomas's mother sent him and his brother to live with their grandfather, Myers Anderson, in Savannah. Life with his grandfather introduced Thomas to much better days which included regular meals and indoor plumbing. Thomas's grandfather also imparted upon his grandsons the importance of a good education. Thomas and his brother worked for their grandfather after school making fuel deliveries. In his spare time, Thomas often went to the local Carnegie library since the Savannah Public Library had not yet allowed blacks to enter. At his grandfather's urgings to become a priest, Thomas left his black high school after two years to attend St. John Vianney Minor Seminary, an all-white boarding school located just outside of Savannah dedicated to training priests. Thomas suffered minor episodes of racism at his new school. His fellow schoolmates excluded him from social activities and made fun of his color. Still, Thomas persevered and graduated with a good academic record.

Thomas attended the Immaculate Conception Seminary in Missouri as his next step towards attaining priesthood. He left soon after, though, due to the severe racism he encountered in the school. After taking some time off, Thomas enrolled at Holy Cross. He participated actively in the formation of the Black Student Union. Thomas also supported the Black Panthers and once urged a student walkout to protest investments in South Africa. In 1971, Thomas graduated ninth in his class with an English honors degree. The following day, he married Kathy Ambush, a student at a nearby Catholic woman's college.

Yale University Law School accepted Thomas through its affirmative action program. While at Yale, Thomas' wife gave birth to his only child, a son named Jamal. Thomas specialized in tax and anti-trust law while at Yale. Upon his graduation, many firms tried to recruit Thomas by hinting at opportunities to do pro bono work. This tactic, however, served only to offend Thomas and he turned every offer down. Thomas decided to return to Missouri to work in the office of then State Attorney General John Danforth. The job allowed him to work in the tax division and did not force his involvement in any civil rights cases. When Danforth won an election to the U.S. Senate three years later in 1977, Thomas left the attorney general's office and became a corporate lawyer in the pesticide and agriculture division of the Monsanto Company.

Thomas left Monsanto after two years and returned to Danforth to work as his legislative aide. When Thomas attended a conference of black conservatives in 1980, a columnist for the Washington Post wrote an article about him that attracted the attention of the Reagan administration.

President Reagan offered Thomas a job as the assistant secretary for civil rights in the Department of Education. Thomas accepted the job and Reagan soon promoted him to head the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC). As the director of EEOC, Thomas supervised the entire federal efforts to curb discrimination in the workplace. Thomas dramatically changed the practice of the EEOC under his leadership. He abandoned the use of timetables and numeric goals, which allowed companies more flexibility in their hiring of minorities. Thomas also ended the use of class action suits that relied on statistical evidence of discriminatory effects. These changes in EEOC practice angered many civil rights groups. During this time, Thomas experienced some personal difficulties. His grandfather died in 1983 and he divorced his wife in 1984. He met Virginia Lamp at a conference two years later and they soon married.

President Bush appointed Thomas to the U.S. Court of Appeals in Washington D.C. in 1990. When Thurgood Marshall retired in 1991, Bush decided to elevateThomas to the Supreme Court. Thomas' nomination met strong opposition from minority groups who opposed Thomas's conservative views on civil rights. Thomas weathered several days of questioning from the Democrat-controlled Senate Judiciary Committee. He was unwilling to express opinions about policies or approaches to constitutional interpretation. He maintained that he had never formulated a position on the controversial abortion decision, Roe v. Wade.

His questioners were unable to shake him. His nomination seemed assured when a last-minute witness, Professor Anita Hill, came forward with charges of sexual misconduct when she worked for Thomas ten years earlier. The nation seemed transfixed by the ensuing testimony of Hill, then Thomas, and a parade of corroborating witnesses who spoke to a national television audience, preempting afternoon soap operas and competing successfully for viewers against the World Series. After a marathon hearing to explore the Hill charges, the Committee failed to unearth convincing proof of Hill's allegations. The Committee reported the Thomas nomination to the full Senate without a recommendation. In the end, the Senate voted 52 to 48 to confirm Thomas's nomination to the High Court.

Since becoming a justice, Thomas has aligned closely with the far right of the Court. He votes most frequently on the same side as the conservative camp of Rehnquist and Scalia. When Thomas began his tenure on the Court, many observers perceived him as a junior version of Scalia. Since then, Thomas has emerged from Scalia's shadow offering hints at his own conservative thinking.

Comments